A new report finds that the impending shift in nonprofit leadership in New England threatens a sector that already suffers from fundamental structural deficits and a lack of investment.

In TSNE’ June 2015 study on nonprofit leadership, “Leadership New England: Essential Shifts for a Thriving Nonprofit Sector,” we found that 64 percent of nonprofit leaders in the region planned to leave their jobs within five years.[1] Thirty percent planned to leave within the next two years. Of the departing leaders, more than one-third planned to retire. These data come from 877 leaders (primarily executive directors) and 330 board members of nonprofit organizations who responded to a survey designed to identify who the current leaders are and the challenges they face.

Impending Transitions

The imminent leadership transitions signal big changes for New England’s nonprofit sector, but the numbers are hardly a surprise. Over the past decade, the literature about the nonprofit sector has been filled with predictions about trends likely to hurt overall effectiveness.[2]

When the Great Recession hit, many of those predictions—the departure of baby boomers, nonprofits closing or merging, and the sector crumbling—did not pan out, but the structural and systemic problems on which the predictions were founded did not go away. As the economy recovers and baby boomers begin to retire in greater numbers, we have so far failed to recognize that such a disruption in nonprofit leadership presents an opportunity to fundamentally change how we invest in our nonprofits, our people, and by extension, our communities. It is time to change the mental model of nonprofits as charities not worthy of serious investment. The new generation of leaders is unlikely to accept that view.

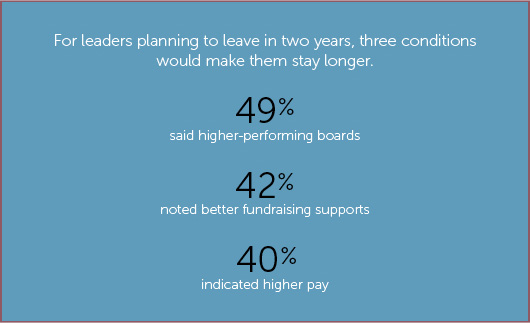

As our report shows, the sector’s success and impact continue to rely on unsustainable factors—overworked, underpaid leaders and staff, for example; struggles to balance budgets and keep organizations stable; a lack of investment in professional development and organizational infrastructure; and conflicting views of the optimal role for nonprofit boards. When leaders planning to leave within the next two years were asked what conditions would make them stay longer, 49 percent said higher-performing boards, 42 percent noted better fundraising supports, and 40 percent indicated higher pay.

Like the impending departure of longtime leaders, none of that is new information. But taken as a whole, a picture emerges of a sector that is chronically undercapitalized and tasked with doing more with less while trying to address problems like poverty, climate change, economic inequality, institutional racism, substance abuse, homelessness, and access to quality health care.

Interestingly, despite the perennial challenges, the sector continues to grow, exhibiting remarkable resilience. Nationwide, the number of nonprofits has shot up since 2008, even adding jobs during the Great Recession.[3] As of late 2014, there were 73,410 reporting nonprofits in New England, up from 44,688 in 2008.[4] If we include new start-ups, benefit corporations, limited-liability corporations, and similar entities working in our communities for social change, it becomes clear that people who see a need in our society and have the wherewithal to start new social enterprises are still doing it.[5] But although some of the new organizations are exhibiting high levels of growth, innovation, and impact, many will face the same struggles indicated by our study.

What Would Change Look Like?

The key overall findings—that leaders and boards are struggling to make ends meet and have little money for professional development and growth—show that the nonprofit leadership picture has changed little over the years.

We know the structural basis for many of these deficits: the nonprofit sector is dramatically undercapitalized compared with the business sector. Businesses use their capital to make improvements in operations and return more money to investors. Nonprofits have few extra resources to invest in increasing their capacity and infrastructure. Their most valuable asset is usually their staff, and many nonprofits need more staff. Of the 877 leaders we surveyed, 51 percent said they have five or fewer employees, and 81 percent have 25 or fewer.

Nonprofit organizations rely on their leaders and employees for their programmatic success and to provide the return on investment (the social capital) that serves the needs of so many in our communities. It should be a concern to all that these organizations continue to struggle. Forty-nine percent of New England leaders say they have three months or less of cash reserves, while 21 percent have one month or less. Sixty-seven percent of leaders make $99,000 or less, and 22 percent make less than $50,000.

The dearth of capital to invest in professional development and other supports for nonprofit leaders also can undermine efforts to build capacity for the next generation of leaders. The private sector spends many more of its resources on leadership development than the nonprofit sector, but in the past 20 years, annual foundation giving for leadership was only 1 percent of total annual giving.[6] Only 54 percent of leaders said their organizations are able to budget for professional development of staff. Leaders report that they have little bench strength: 60 percent of organizations report they have no succession plan in place.

Of course, there is another side to the story. The fact that 88 percent of the leaders surveyed in our study report that they’re happy or very happy in their jobs despite the challenges offers some insight. They told us they feel appreciated, challenged, and fulfilled by their mission-related work. But although they and the staff they lead are the sector’s most valuable assets, we have somehow created a system that relies on the willingness of such committed people to accept low pay and little investment in their professional development. Ultimately, some may decide that that state of affairs hurts the causes they so passionately espouse.

How long can this go on? We expect a lot from our nonprofit leaders, but despite the fact that investment in overhead, salaries, and leadership development is minimal, the media and the public often imagine that leaders are paid exorbitant salaries.

It’s time the nonprofit sector and its funders raised the bar. Nonprofit leaders may define success as being “stable”—but stable is not enough. For leaders to be truly effective, they need enough financial support to allow them to learn, reflect, and innovate. They need time to develop their staff and to make plans for the future. They need to engage in deep learning about leadership development and to understand how their organizations can achieve mission impact. Our study showed that leaders are significantly more likely to think their organization has the capacity and bench strength to handle a leadership transition when staff have resources committed to professional development.

If our primary funders and capacity builders (foundations or intermediaries like Boston-based TSNE, Bridgespan, and FSG) helped organizations invest more in what leaders say they need to do—build higher-performing boards, create succession plans grounded in a long-term vision for sustainability, achieve financial stability, strengthen the leadership skills of their staff, and work in more collaborative and networked contexts—they would accomplish more with their dollars and yield more of the social capital the sector returns to its supporters. With broad and strategic investment in the capacity of organizations and their people, the sector could become more resilient, address social inequities better, and deliver more on the promise of strengthening communities.

Endnotes

- Hez G. Norton and Deborah S. Linnell, “Leadership New England: Essential Shifts for a Thriving Nonprofit Sector” (report, TSNE, Boston, 2015), http://tsne.org/leadership-new-england.

- See the “Daring to Lead” series by CompassPoint Nonprofit Services (2001, 2006, 2011), www.compasspoint.org.

- Lester M. Salamon, S. Wojciech Sokolowski, and Stephanie L. Geller, “Holding the Fort” (Nonprofit Employment Bulletin no. 39, Johns Hopkins University Economic Data Project, Baltimore, 2012), http://ccss.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/01/NED_National_2012.pdf.

- “The Number and Finances of All Registered 501(c) Nonprofits” (report, The Urban Institute, National Center for Charitable Statistics, Washington, DC), http://nccsweb.urban.org/.

- Since the law first passed in Maryland in 2010, 30 states and Washington, DC, have passed legislation permitting benefit corporations, a class of corporation that voluntarily meets different standards of corporate purpose, accountability, and transparency. See benefitcorp.net/faq.

- The for-profit sector invests $129 per employee per year in leadership development; the civic/social sector invests $29. See Niki Jagpal and Ryan Schlegel, “Cultivating Nonprofit Leadership: A (Missed?) Philanthropic Opportunity” (report, National Council for Responsive Philanthropy, Washington, DC, 2015), http://ncrp.org/paib/smashing-silos-in-philanthropy/cultivating-nonprofit-leadership; and Laura Callahan, “Under-Investing in Social Sector Leadership” (report, Common Good Careers, Boston, 2014), http://commongoodcareers.org/articles/detail/guest-article-under-investing-in-social-sector-leadership.

(This article was originally written for the Spring 2016 Community & Banking newsletter of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement.)